2. Pathogenesis

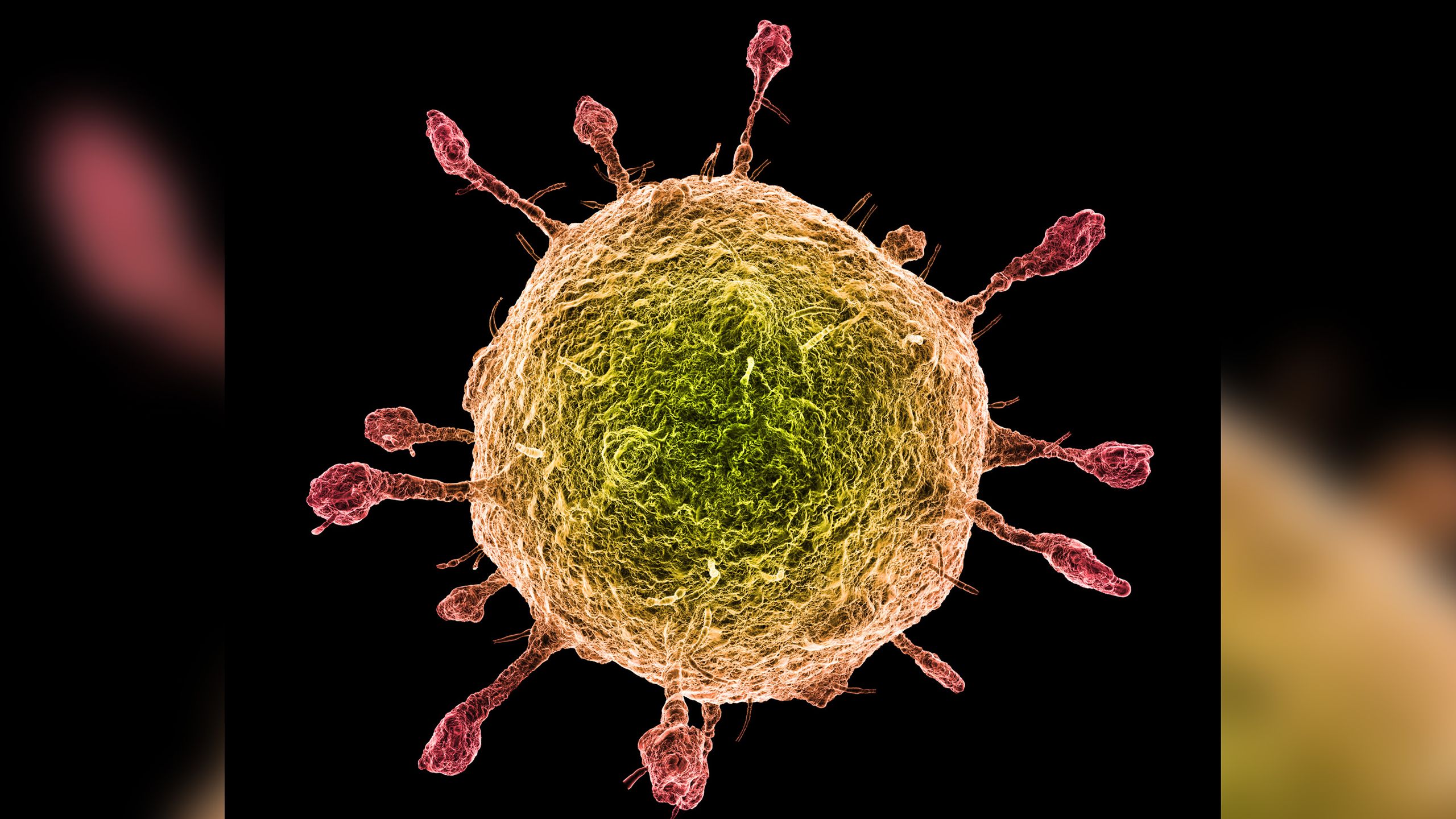

Filoviruses have a broad cell tropism, infecting a wide range of cell types. This tropism is directed by its envelope glycoprotein (GP). Dendritic cells, monocytes, macrophages, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, hepatocytes, adrenal cortical cells, and several types of epithelial cells support the replication of these viruses [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages are preferred as early replication sites of EBOV. Together with neutrophils these cells play pivotal roles in dissemination or trafficking of the virus as it spreads from the initial infection site to regional lymph nodes, probably through the lymphatic system, and to the liver and spleen through the blood. EBOV also affects tissues notably liver, spleen, kidneys, lymph nodes, testes, gastrointestinal mucosa, lungs and skin and causes extensive tissue necrosis [

22,

23,

24]. Infection with EBOV first causes a significant inflammatory response and lymphoid cell apoptosis (most likely due to release of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α)), which leads to lymphopenia [

2,

25] and suppression of effective adaptive immune response [

26]. Moreover, inhibition of the type I interferon response, one of the major anti-viral host defenses, is another important aspect in the pathogenesis of the disease [

19,

27]. In addition, viral replication in monocytes elicits a storm of pro-inflammatory cytokines. By doing so, the virus disables the immune system, allowing uncontrolled viral replication and dissemination and indirectly damages the vascular system that leads to hemorrhage, hypotension, thrombus and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) followed by shock, organ failure and death [

19,

27]. Coagulation abnormalities associated with EBOV are not the direct result of virus-induced cytolysis of endothelial cells, and are likely triggered by immune-mediated mechanisms [

28]. In experimentally infected animal models or in naturally infected Ebola patients, increased blood concentrations of nitric oxide were associated with mortality [

29] because its abnormal production can induce several pathological disorders including apoptosis of bystander lymphocytes, tissue damage and loss of vascular integrity, which might contribute to virus-induced shock [

19].

EBOV also causes extensive hepatocellular necrosis with a concomitant reduction in the formation of coagulation proteins. It also affects the adrenal gland and destroys the ability of the patient to synthesize steroids and aggravate the circulatory failure by disabling blood pressure homeostasis [

1,

2]. In the heart, lungs, intestine and pancreas, impairment of the microcirculatory bed is seen but actual necrotic lesions are rare [

30]. In general, the ability of EBOV to disable such major mechanisms in the body facilitates the ability of the virus to replicate in an uncontrolled fashion leading to the rapidity by which the virus can cause lethality [

2].

www.livescience.com