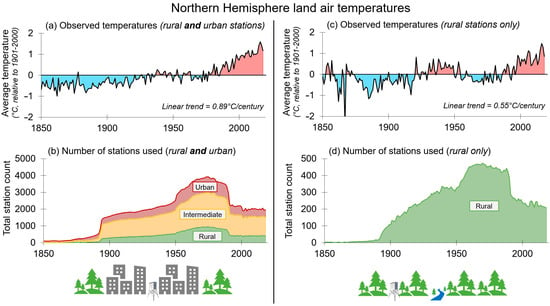

To reduce the amount of nonclimatic biases of air temperature in each weather station’s record by comparing it with neighboring stations, global land surface air temperature datasets are routinely adjusted using statistical homogenization to minimize such biases. However, homogenization can unintentionally introduce new nonclimatic biases due to an often-overlooked statistical problem known as “urban blending” or “aliasing of trend biases.” This issue arises when the homogenization process inadvertently mixes urbanization biases of neighboring stations into the adjustments applied to each station record. As a result, urbanization biases of the original unhomogenized temperature records are spread throughout the homogenized data. To evaluate the extent of this phenomenon, the homogenized temperature data for two countries (Japan and the United States) are analyzed. Using the Japanese stations in the widely used Global Historical Climatology Network (GHCN) dataset, it is first confirmed that the unhomogenized Japanese temperature data are strongly affected by urbanization bias (possibly ∼60% of the long-term warming). The U.S. Historical Climatology Network (USHCN) dataset contains a relatively large amount of long, rural station records and therefore is less affected by urbanization bias. Nonetheless, even for this relatively rural dataset, urbanization bias could account for ∼20% of the long-term warming. It is then shown that urban blending is a major problem for the homogenized data for both countries. The IPCC’s estimate of urbanization bias in the global temperature data based on homogenized temperature records may have been low as a result of urban blending. Recommendations on how future homogenization efforts could be modified to reduce urban blending are discussed.